- Home

- Allen Wold

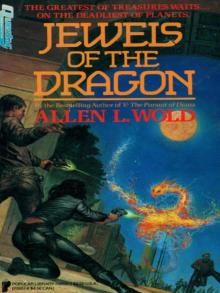

Jewels of the Dragon

Jewels of the Dragon Read online

Jewels

of the

Dragon

Rikard Braeth

Book I

Allen Wold

As always, for Diane, my best critic,

but especially in memory of my father.

Contents

Part One

1

2

3

4

Part Two

1

2

3

4

5

Part Three

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Part Four

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Part Five

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Part Six

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Part Seven

1

2

3

4

5

Part Eight

1

2

3

4

5

Part Nine

1

2

3

Part Ten

1

2

3

4

5

Part One

1

Kohltri was a lonely planet, the only one orbiting its sun, and far from the rest of the Federation, of which it was a member.

Across the Federation from Kohltri were the Crescent Cluster, the Anarchy of Raas, the Abogarn Hegemony, and other political entities spanning dozens or hundreds of inhabited star systems. But on this side there were only the great reaches between this spiral arm of the galaxy and the next. Not truly empty, but there were too few stars and those too far apart to entice expansion.

Kohltri Station, as a consequence, was small. It circled the planet in geostationary orbit 33,000 kilometers above the surface. Its hundred thousand people administered the planet and its commerce, or provided services for the administrators. Station time was set to the surface immediately below it. When the station passed into Kohltri's shadow, it was night.

Now it was nearly noon. Rikard Braeth, twenty-six in Earth years, stood at the door to the station director's office. He was very tall, very slender, and moved with a grace that sometimes made him seem lazy. His skin was dark, his hair black and rather unruly. He was not handsome, and his clothes, once good, were now old.

After the briefest of pauses, he reached out and touched the latch plate beside the door. The door slid open and he went in.

The office was not large. In the middle stood a small, immaculate desk behind which sat the Director, head bent over the several screens embedded in the desk's surface. According to the brass plate at the front of the desk, the Director's name was Anton Solvay.

On the wall behind Solvay were framed credentials and certificates. The entire left wall,of the office was a huge window, showing the deeps of space outside the station. The limb of the galaxy cut a messy diagonal across one corner. On the right wall communications equipment and reference shelves bracketed a private door.

Solvay punched a few buttons, some screens cleared, and only then did he look up. He was a compact man, slightly balding, and somewhere in his fifties—still young, given a life span of about two hundred years. He rose to his feet and extended his right hand. He was fully a head shorter than Rikard.

"Msr. Braeth," he said as he shook Rikard's hand. "Welcome to Kohltri Station." He waved his hand toward one of the two chairs in front of his desk, an invitation to sit. "What can I do for you?"

"It's just a small matter," Rikard said, taking a seat. "I'm sorry to trouble you about it, but I don't know who else to ask. I need to go down to the surface of Kohltri, and I haven't been able to find out how to do that."

Solvay sat back, a look of mild surprise on his face. "Why in heaven's name would you want to go down to the surface?"

"I'm looking for my father. I've traced his movements all the way from Pelgrane to here. It's taken me two years."

"And you think he went to the surface?"

"I do. My father was very methodical. On every one of the sixty or so worlds I've tracked him through, his pattern was always the same. He'd come to a world, visit the University Central if there was one, the major museums, and so on, and always the Mines and Minerals Reclamation office. And since the Mines office is on the surface, that's where my father would have gone after he'd finished up here."

Solvay drummed his fingers lightly on the desk. "Exactly when was this?" he asked.

"Rather a long time ago, I'm afraid. My father left home thirteen years ago. Your records show he arrived here about two years later."

"And you were able to follow him here after waiting eleven years? Remarkable. But records like that are not generally available for public inspection. What authority do you have to search them?"

"I'm a Local Historian, accredited by the University of Pelgrane. Getting my degree was part of the reason that it took me so long to start looking for my father."

"I see. And you found a record of your father on a shuttle list?"

"No, but then I haven't found any record of his departure, death, or naturalization either. And he always visited the Mines offices. The surface is the only place he could have gone."

"I see." For some reason Solvay did not seem very pleased. "That is certainly a reasonable conclusion. I wish I could help you, but I can't."

"In that case," Rikard said, "could you tell me who can? I'm willing to pay for a special shuttle trip, if that's necessary."

"No," Solvay said, "I mean you can't go to the surface."

"Why not?" Rikard made sure his voice revealed no emotion other than simple curiosity.

"You don't have the proper clearances."

Rikard sighed. This was not the first time he'd had to deal with the vagaries of a bureaucracy. He took his wallet from his inside jacket pocket, took out his Historian's Accreditization Card, and handed it to the Director. That card had gotten him into a lot of places other people didn't think he had any right to. Solvay looked over the card, examined the holographic representations, dropped it on the ID plate on his desk to check the readout.

"I hope," Rikard said, "that that will prove satisfactory."

"I'm sure that it would almost anywhere but here." Solvay handed back the card. "You are free, of course, to examine any records that are not restricted by law, but I cannot let you go down."

"I don't understand," Rikard said as he put his card away. "Kohltri is not on any of the military registers. Why can't I go to the surface?"

"I am not at liberty to tell you that. The very fact that you don't know why you can't go down is proof that you have no business on Kohltri. If you want to go to the surface, you'll have to get authorization elsewhere."

"Ah, all right. I think I can still afford a round trip. Where should I go, and what kind of clearances do I need?"

"Again, if you don't already know, then I'm not at liberty to tell you. I'm sorry."

"Msr. Solvay, this doesn't make any sense. I know that a lot of people come here—"

"Not a lot, only a couple hundred a year."

"Close to a thousand, according to your own records. And most of those people go to the surface, as far as I can tell."

"If they go down, that's only because they have p

roper clearance."

"I didn't see anything about any clearance in the records."

"Of course you didn't; you weren't supposed to. It's not good security to label secret things as secret."

Rikard felt his frustration rise. This conversation wasn't getting him anywhere. He decided to try another track.

"Kohltri," he said, "is a mining world, as I understand it."

"Yes, it is."

"The records aren't always very clear on just what is mined here."

"That's true. Look, we're a long way off from the next nearest system. That means we're vulnerable to certain kinds of industrial espionage. We keep a low profile, in large part as a matter of self-defense. I can't tell you anything more than that."

"You mean to say that the ores you mine here are classified information?"

"You've see the records, apparently."

"Some of them," Rikard said, "yes. Does it matter that I have absolutely no interest in your mines?"

"None at all. I'm sorry." Solvay got to his feet, indicating that the interview was over.

"I am too," Rikard said, also rising.

"If there's anything else..." Solvay suggested, extending his hand again.

"Nothing right now." Rikard shook Solvay's hand out of courtesy. He turned and went out of the office. He went mrough the outer offices of the administrative section and out into the corridors of the main part of the station.

"Damn," he muttered to himself. He could feel his face getting hot, and the sound of his teeth grating was loud in his ears. He knew about security, what files were classified and what weren't. Nothing he'd looked at had any restrictions at all.

He saw someone staring at him in alarm, and others moving discreetly to the side of the corridor. Very deliberately, he made his face bland and tried to suppress his frustration and anger.

2

Rikard wanted to get as far away from Solvay's office as possible. He walked along the corridors of the station with that intent, heading for the far end. As he walked, he worked to put Solvay from his mind, to make himself feel as calm as he now looked. But as his composure returned, he became aware that the scar on the palm of his right hand was itching. He tried not to scratch.

He ignored the other people in the corridors, and they mostly ignored him, though a person as tall as he was always drew some attention. He managed to ignore his thoughts of Solvay as well, but now the tingling in his palm became stronger. However calm he'd made his surface, he was still suffering from internal stress and tension.

That was when the scar itched. It wasn't much to see, just a slightly irregular line from his ring finger to the base of his thumb. Thinking about it now made the itching almost painful. Gently, he rubbed it with the thumb of his left hand.

He hated to yield, because rubbing or scratching the scar produced a strange secondary effect, bringing a momentary impression of concentric circles swimming in his eyes.

The image never came when he was calm, no matter what work he was doing with his hands. Only when he was angry did the scar itch, and only when he scratched the itch did the rings appear—a visual and mental distraction. They were as hard to see as the motes in his eye, circling the center of his field of vision. If he tried to focus on the rings, they shifted and faded.

This time the circles were so strong that he knew his inner turmoil was only barely controlled. And the visual illusion and the itching scar were not helping him calm himself. After all, the cause of his frustration and the cause of the scar were the same. It was his father he was looking for, and it was his father who had given him the scar with its phantom rings in the first place.

Back on Pelgrane, when he was just ten years old, his father took him to a clinic and paid a lot of money for an unusual operation, then paid a lot more to keep the fact of the operation discreet. The surgeons had implanted a small device in Rikard's palm, a device his father had found somewhere, that was somehow supposed to have given Rikard better than average skills with a gun. Guns had been his father's one indulgence, the only thing, Rikard now knew, that he had retained from his life before Pelgrane.

The device in his palm was connected by artificial nerves running up his arm directly to the visual centers of his brain where it caused the images of circles. But it didn't seem to work otherwise; Rikard had no special advantage as a marksman. The surgeons had checked the medical aspects of the operation, but the device itself was strange to them. Even his father had not fully understood the mechanism and had been sorely disappointed by the apparent failure of the costly operation.

In later years, after his father abandoned his family, Rikard had grown to hate the scar for what it represented. For a while he had contemplated having the device removed, but he hadn't had the money then. Later, when he could afford it, he'd decided he had better things to do with the money. And so the device, the scar, and the circles remained.

Now those circles added to his anger, undermined his attempts to calm himself. He clenched his hand and stuffed it in his pocket. Let it itch; he wouldn't scratch, and then maybe he could calm down.

He walked through the middle levels of the station, the residential levels. Science was "above," industry and service "below." There were more people man when he'd gone to the Director's office. It must be the local lunchtime.

His stomach confirmed that, even as he checked his watch. He could eat at his hostel, but then he would be alone with his thoughts, and he didn't want that. Instead he walked on to the far end of the station, to the clubs, shops and recreation areas.

He wandered off the main ways, looking for something suited to his mood, until he noticed the marquee of a tavern, situated up a side corridor. A couple of beers, he thought, were just what he wanted right now. He went to the tavern door and stepped inside.

It was not as dim as many such places, and fortunately also served sandwiches. Most of the customers were seated at the few small tables between the bar and the booths against the window wall. Through the window Rikard could see the black velvet of space, the stars above and below. From this part of the station he could even see a bit of the planet.

He'd come here for company, so he looked around for someone on whom he could impose, and was pleased to notice a man whom he'd seen several times during the last few days. A familiar face might be more willing to put up with an unexpected lunch partner than a total stranger would be, so Rikard went up to introduce himself.

The man watched Rikard approach. He was a few years older than Rikard but looked as if he'd seen a lot more of the world. He was handsome in the way that Rikard had admired as a kid, the way he'd futilely hoped he'd look. Rikard stopped by the empty chair across from the man and smiled.

"We've not met," Rikard said by way of greeting, "but I've seen you in the records office several times, haven't I?"

"You have indeed," the man said. He seemed rather reserved, but did not object to Rikard's presence.

"Do you mind if I join you?" Rikard asked. "I'm tired of eating alone."

"By all means," the man said, rising to his feet. He was as tall as Rikard but muscular instead of slender. He extended his hand toward the empty chair in a gesture of hospitality. "Please sit down." His tone and words were polite, but there was an underlying tension Rikard had noticed before.

"I'm not intruding, am I?"

"Not at all. I'm Leonid Polski."

"Rikard Braeth," Rikard said, shaking his hand.

When he sat, the table flipped up its menu. Rikard punched in his selection and credit ID, and the menu slid down. Immediately, the service slot in the tabletop slid open and his sandwich and a pitcher of beer came up.

"You must be new to Kohltri Station," Polski said. Though he seemed friendly, Rikard got the impression that he was never truly relaxed.

"I've only been here three days," Rikard admitted. He poured beer into his glass and offered to refill Polski's.

"No thanks," Polski said. "What brings you to an out-of-the-way place like this?"

"That's strange. Did he say why?"

"No, and that's what's so infuriating. Here I've come almost all the way across the Federation, and I know the end of the trail is down on the surface, and now I'm blocked."

"That would be rather frustrating, I imagine."

"To say the least. Solvay says I don't have the right clearances, and then won't tell me what those are or how to get them. Would you know anything about that?"

"Sorry," Polski said with a slight smile. "I've only been here nine days myself."

"Are you going to be working here?"

"I'm afraid I can't talk about it," Polski said. He took his wallet out of his jacket pocket, flipped it open, and showed Rikard the badge of a Federal Police Officer. He held the rank of colonel, and an attached emblem identified him as a special investigator.

"Just forget I asked," Rikard said. "But I'll bet Director Solvay doesn't treat you the way he does me."

Polski put the wallet away. "I don't have any problems with him," he said.

Rikard concentrated on his sandwich for a moment. "If it's not prying," he said, "can you tell me anything about these clearances Solvay mentioned?"

"I really don't know anything about them."

"I just thought that as a police officer.. .Oh, well, I'll figure something out."

"Forgive my curiosity," Polski said, "but are you by any chance related to Arin Braeth?"

Rikard put down his sandwich, suddenly wary. "He's my father," he said. "Are you looking for him too?"

"No," Polski said with another soft smile. "No, it's just that I studied your father at the Academy."

"My father went out of circulation thirty years ago."

"I know, dropped completely out of sight, no clue or word of him since."

"And yet you studied him at the Academy."

"Him and others like him, though Arin Braeth was always my favorite."

Rikard kept his voice calm and even. "You know," he said, "as a kid I never really knew what my father did before he met my mother. It wasn't until I went out exploiting, to pay my way through the university, that I ever heard anything about his past. Since men, I've heard people call him all kinds of things. But to me he was just my father, even if I didn't always understand him."

V: The Crivit Experiment

V: The Crivit Experiment The Pursuit of Diana

The Pursuit of Diana Jewels of the Dragon

Jewels of the Dragon Lair of the Cyclops

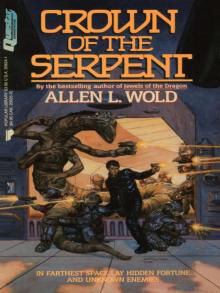

Lair of the Cyclops Crown of the Serpent

Crown of the Serpent