- Home

- Allen Wold

Jewels of the Dragon Page 2

Jewels of the Dragon Read online

Page 2

"You said he left home more than eleven years ago? You must have been quite young then."

"It was my thirteenth birthday."

"Not a very pleasant birthday present, I imagine."

"No." He finished his beer and poured another glass. "The money had run out. And he didn't like being poor. He told my mother he was going to try to make one more score—I didn't know what that meant then—but he never came back."

"And you think he's here now."

"Maybe I don't, after all."

Polski considered him a moment. "Rikard," he said, "I'm not after your father. As far as I know, nobody is any more. And even if they found him here, there's nothing anybody could do about it."

"I guess after thirty years the statute of limitations does run out."

"On most things, yes. Not on someone like the Man Who Killed Banatree, of course. But that's not the point. In spite of all the stories about him, your father was never indicted— for anything. There's no doubt in my mind that he did the things he's credited with, at least most of them. We're also sure he did other things we know nothing about and may be responsible for things with which he's not been connected. But the thing that makes Arin Braeth so special, the reason he's the subject of an entire semester's course, is that there is not one shred of evidence against him. And without that, who's to make an arrest?"

"You almost sound as if you admire him."

"I do. In a way. We're sure he was responsible for some of the most daring crimes and exploits of the last two hundred years. Your father was known as a pirate, among other things, feared through half the Federation. His reputation extended into the Crescent Cluster, and even the Abogara Hegemony. And yet, there was never any proof. Was he, or wasn't he, the man of the legends? If he was, how did he get away with it? If he wasn't, how did he get such a reputation?"

Rikard smiled sardonically. "Father didn't let me in on any of his secrets."

"To have gotten away as clean as he did, whatever the truth, he couldn't have trusted anybody. Not even your mother, I'll bet."

"He trusted her with everything except the details of his past. As far as I know."

"She knew what kind of man he was?"

"Oh, yes."

"She must be quite a woman to have made him change his ways so radically."

"She was. She died three years after he ran off. It broke her heart."

"I'm sorry. You hate him for that?"

"Not as much as I used to." He picked up his sandwich and had another bite. "I'm older now. I have a better perspective. Whatever anybody says about him, whatever the truth may be, when I knew him he was just a fine man, a fine father. He was well liked on Pelgrane, served several times on our city council, and had lots of friends who stuck with him even after the money ran out. But that wasn't enough for him."

"And now you've come looking for him."

"I want to find out what happened, why he didn't come back. I suspect that he died down there on Kohltri. I just want to know for sure, find his grave if I can. I wish I could make Solvay understand that."

"As I remember the story, just before he disappeared, he rescued the Lady Sigra Malvrone from one of the most hideous kidnapping and extortion rings in existence."

"The Lady Sigra was my mother. Her father, Lord Malvrone, knew about my father and hired him to get my mother away from the kidnappers. When Father brought her back, Lord Malvrone refused to pay. Just shut Father out completely.

"What he didn't figure on was that my parents had fallen in love, and Mother just decided to hell with her family and went off with my father. They had enough money between them so that my father could retire. Until his investments went wrong, we lived just like any other middle-class family. My mother gave up her past too."

"So what are you going to do now?" Polski asked.

"I'm not sure, but I haven't exhausted the records office yet. Right now I'm going to finish this beer, maybe have another, take a long nap, and then do a little more research, just to see what I can dig up."

"Don't dig up any trouble," Polski said.

3

Kohltri Station, as small as it was, did not have to operate around the clock. Rikard waited until the night shift was two hours old, with only a skeleton staff on duty, before returning to the records office. Though he preferred not to do anything illegal, he didn't want to be observed should the necessity present itself. As a Historian, he had every right to make use of the facilities, even at this hour, but he would not let any mere legality impede him if he found something interesting.

The offices were locked at this hour, but his authorization card unlocked the door without a hitch. The place was half dark, which meant there was no staff present to glance casually over his shoulder at the readout screens.

He walked through the outer offices, past the cubicles used by government workers, and into the hall of regular consoles.

He looked into every room, even the closets and restrooms. That, he now knew, was what his father would have done. When he was sure there really was nobody else in the office complex, he went back to the main hall and took the console farthest from the door. It was in a comer where, by turning his head, he could see the whole room. That, too, was what his father would have done.

Rikard knew very little about Kohltri other than that it was one of those places where all or most of the business was done on the station. The planet itself merely provided raw materials. In this case those were ores rather than woods, fibers, organics, spices, or whatever. He called up the index, scanned it quickly, and chose a recent report on the planet's nature and resources.

There was only one city, just called Kohltri, directly below the station, population not specified. There were mines whose products he did not recognize. There were imports of equipment, much of it unspecified or identified in code. The main export was refined ore. All the references were unusually cryptic, and he wasn't much interested in mines. But this was a good set of files to revert to if someone should come in. He precoded a call so that he could switch in a hurry if he had to.

Once again he examined the records of his father's arrival and residency. This time he compared them with his own similar records and with those of other visitors at various times during the last twenty years. He was looking for any code or sign that distinguished either his father or himself from the people who had gone down to the surface. He could find none, no clue as to who had clearance or what clearance was.

The records of interstellar movement of people and goods were remarkably thorough—if sometimes cryptic, obscured by bureaucracy, blurred by time, and full of jargon. They hinted at unusual things about business transactions between Kohltri Station, the surface, and other worlds, though only a Historian would notice. Every world had its irregularities, but he wasn't interested in them at the moment. He skimmed through the records, then called for the lists of those who had departed Kohltri for other systems.

A message appeared on the screen, asking for his authorization code. He keyed in his Historian's registration and was immediately given access.

The lists up through this very day produced no evidence that his father had ever left the Kohltri system. He closed that file and opened another. It came on-line without a pause.

And it told him that at no time, from the moment of his father's arrival up to this afternoon, had he or anybody Rikard could identify as him applied for or been given permanent residence on the station. That was an unlikely possibility, but it closed another loophole. There was just one other major file to double-check. He called it up.

The death records were similarly complete. Rikard's father had not died on the station. A quick scan of a related file showed also that he had not been arrested. Rikard closed that file too and sat staring at the prompt on the screen.

The records of his father's two-year trip across the Federation had revealed very little about what he had been looking for. That it could make him rich, Rikard had no doubt, and if his father had fou

nd it, Rikard wanted his share. His father, alive or dead, owed it to him.

He had only one thing to go on: wherever his father had gone, whatever other offices he might have visited, he had always checked with the Mines and Minerals Reclamation office. Rikard had seen the record of his father's inquiry about the Mines office here, but that was on the surface.

Arin Braeth would not have left Kohltri without going down to the surface to investigate it in person. If Rikard could have followed, he wouldn't have to be doing what he was doing now.

He queried the computer for the records of the shuttle flights; they had to contain the information he needed. Once again he had to post his authorization. As before, access was immediately granted.

At first this list seemed just the same as the others, but as he read through it, he saw that it was in fact quite different. A few of the passengers to the surface were identified as government officials with specified business. A few others were coded, obviously for security reasons. All these showed a cross-reference to a list of people returning from the surface.

But they were the minority. Most of the shuttle passengers appeared to have come from other systems rather than from the station population, but they had no return-entry reference. Neither did their names appear on the list of those who had come from other systems. The two lists did not correspond.

Far more people went down than came up, and those few who did return to the station from the surface, aside from official and coded passengers, were not the same as those who had gone down in the first place.

These anomalies didn't help him with his original problem, though. There was nothing in any of the records to indicate who had clearance or what it was.

Within twenty-four hours after Rikard's father had checked out of his hostel, six people had gone to the surface. None was listed as Arin Braeth. He could have assumed a false identity, but it would have been for the first time since leaving Pelgrane.

Just to see what he might turn up, Rikard made a copy file of those six people, including all codes, abbreviated references, and data keys, then exited the shuttle file and set up a larger search among all the other files he had examined, hoping to shake out a pattern. These six people must have had that mysterious clearance, and if Rikard could learn what it meant in their cases, he might be able to fake clearance for himself. With or without Solvay's knowledge or approval.

Before the search could produce anything, several messages flashed on the screen simultaneously. The search could not continue without entry into other files, restricted files.

He sat back to think for a minute. So far everything he'd done had been perfectly proper and legal. This was as far as his certificate entitled him to go. But he was too close to quit now.

His specialty at the university had been research methods, and his greatest interest was accessing ancient or faulty files— or secured files. He had gone beyond the curriculum, using the questionable methods he developed to discover still others. Now, perhaps, was the time to use his bag of dirty tricks in earnest. If he was careful, if he still had the knack, no one would ever know that he'd broken the station's security.

He keyed in a request to access one of the restricted files, one he hoped would tell him more about those six people eleven years ago. As expected, he got a message asking for his security code. Just to test it, he tried his Historian's registration. It didn't work. Then he started using his unorthodox tricks. It was like sneaking in the back door, finding a path that was bizarre enough to be unguarded. After several sideways movements and subtly off-key requests, he was into the restricted files. That was what he liked.

The list was more or less as he had expected, with entries for his six people, but he could make little sense of the rest of it. There were numerous cross-references, but whether they were to people, places, products, or events he could not tell. Still, in what he could understand, there was nothing to make him believe that any of the six was his father.

He requested a similar file for the following day and was not asked again for a security code. This file was like the first and contained nothing more intelligible or interesting. He checked the next three days and still learned nothing. On a hunch he tried the previous day. Nothing.

He worked his way into one of the other restricted files, one concerning people coming up from the surface. It was just as cryptic, mysterious, and confusing as the first. No clues.

He tried another sequence of files, reporting on shipments of goods from the station to the surface. One of them seemed to list ground transport vehicles, with some references which made little sense, apparently for secondhand vehicles but with price differentials that were completely out of line, even for a government contract. And the credit accounts were not in the form of the government codes he was familiar with.

Something called "balktapline" was mentioned once or twice. The entries, with the transporter given a code instead of a name, the lack of any destination, and price or value being in another code, suggested that it was some kind of contraband, maybe narcotics, black-market items, or locally illegal products.

That was none of his business, but if Solvay's clearances had to do with smuggling, it was no wonder that he didn't want Rikard going down to the surface where he could learn more. Rikard found the thought amusing. Solvay had nothing to fear from him; it was Leonid Polski who was the threat. Was that why Polski was here? Rikard didn't really care.

He skimmed through a few other files, but could make no more sense of any of them. There were shipping lists, passenger lists, and sometimes hints of transport to and from the surface that did not go through the station. The entries were obscure, partly in code, and with the cryptic cross-references that were now becoming familiar. There was plenty of material to look through, but the night shift was running out. He'd have to quit soon and plan to come back later.

He was not so completely absorbed in his work that he did not hear an outer office door opening. He listened for a moment, his fingers above the keyboard. There was a pause, then he heard the door close softly. Whoever was there had not meant him to hear.

He cleared the screen and called up the public files he'd set up for cover, the ones concerning Kohltri's production and shipping of ores. He heard a soft footstep at the door to the console hall. He called up reference material on the kinds of ores Kohltri produced. The door opened, but he did not look up from the screen. Instead he pretended to be absorbed in the document, though the words went right through his consciousness without stopping.

From the corner of his eye, he could see a woman standing in the doorway, watching him. He took his hands from the keyboard, leaned back, and continued to read. When she started to come toward him, he looked up, carefully feigning mild surprise.

The woman was maybe forty, well built, good-looking, dressed in blouse and slacks. But she had a hard face and a stiff tension that reminded Rikard of Leonid Polski, though somehow she was harder and colder.

She walked right toward him. Rikard watched her, not touching the keyboard. She would be able to see clearly that it showed a perfectly innocent file.

"You're Rikard Braeth?" she said, not really a question. Her voice was mellow but emotionless, her face expressionless; her eyes revealed nothing.

"Yes, I am," Rikard said through a long and very real yawn.

"Up kind of late, aren't you?"

"I couldn't sleep. I thought I might as well find out a little more about Kohltri's mines."

"Indeed. Someone's been looking into restricted files. That wouldn't be you, would it?"

Rikard pushed his chair back. "Look for yourself," he said.

She didn't bother to look at the screen, just kept her eyes fixed on him. Rikard affected an expression of puzzlement and offended innocence.

"You switched files," she said, "just as soon as I entered the outer office. You're pretty good."

"I don't know what you're talking about."

"Of course you do. But it doesn't matter. Direct

or Solvay wants to see you, right now."

Rikard fought to control his tension. "What if I don't want to see him?" he asked.

She moved her right hand behind her to the small of her back. "Then I'll have to carry you," she said, and brought her hand back into view. She held the conical spindle shape of a police jolter.

Rikard stared at it for a moment. "I'd rather walk."

4

The corridors of the station were empty. The woman walked a little behind Rikard and to his left, giving him no chance to get away or attack her. She didn't say anything, and Rikard didn't try to question her. Though she wore civilian clothes, she had to be part of the station's police force. Rikard was sure she could be quite dangerous.

She did not signal their arrival at the office, just palmed the door open. Inside were two other officers, in local uniform, one on either side of the desk. Their jokers were prominently displayed on hip holsters. As the door slid shut, the woman put hers away and nudged Rikard forward to stand in front of Solvay's desk, then stepped back out of Rikard's sight.

After a moment the private door opened and Anton Solvay came in. He stared at Rikard as he moved to his desk. His face was grim.

He sat; Rikard remained standing. Solvay said, "You think you're pretty clever, don't you?"

Rikard returned the man's gaze. He kept his anxiety out of his face and said nothing.

"You have to be clever," Solvay went on, "to be able to gain access to restricted files."

"I was looking at Kohltri's history and products files," Rikard said.

"Yes," Solvay said, "when Msr. Zakroyan walked in on you, but not before. When certain restricted files are accessed, even by me, an alarm sounds and subsequent use of the files is tracked for later audit. So we know damn well what you were looking at in there."

Silence was better than a futile denial, but Rikard's palm started to itch.

V: The Crivit Experiment

V: The Crivit Experiment The Pursuit of Diana

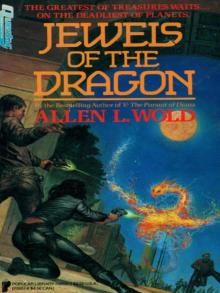

The Pursuit of Diana Jewels of the Dragon

Jewels of the Dragon Lair of the Cyclops

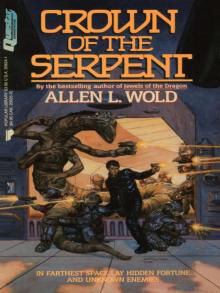

Lair of the Cyclops Crown of the Serpent

Crown of the Serpent